Of all the people Leon Trotsky met during his 1917 ten-week stay in New York City, few were more personally hostile then Grisha Ziv.

Ziv had known Trotsky back in Russia when they were both teenagers, was arrested with Trotsky in 1898 when their youthful circle of friends helped organize an illegal workers’ union in the industrial Black Sea town of Nikolaev, was sentenced with Trotsky to exile in Siberia, and knew the woman Alexandra Sokolovskaya Bornstein who Trotsky married behind bars awaiting sentence.

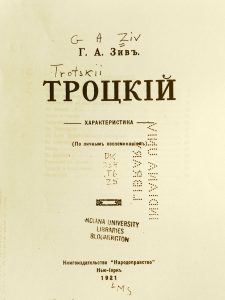

Ziv published a Russian-language book about Trotsky in 1921 that contained a rare account of his interactions with the future Russian Bolshevik leader in 1917. I had the account translated into English as part of the research on my book TROTSKY in NEW YORK, 1917 . As a service to future researchers, I am posting the full text of the translation below.

From Trotskii: Testimony as to Character

by G.A.Ziv

Narodoprevstvo Publishing House, New York, 1920:

Chapter 10

IN AMERICA

Meeting in New York. – Speeches about the “Immediate Ceasefire on the Fronts.” – “The Reactionary Imperialist Entente” and “Progressive” Germany. – The Forthcoming “World Revolution.”

Once it became apparent that Trotsky was coming to New York, all of the local socialist newspapers started their campaign to prepare the general public to properly welcome the guest.

The circumstances were more than favorable for this campaign to be executed on a large scale, the way they do it in America: an old advocate for Russian freedom and democracy (Trotsky has always been a supporter of democracy and freedom), a socialist and revolutionary, who had been deported from Austria, not allowed into Germany, persecuted in Spain and France, oppressed all around Europe for his selfless dedication to the idea of peace, was very appealing to the anti-militarist audiences of the socialists newspapers, which kept their readers on their toes by providing the newest information of Trotsky’s past and present activities.

Not only Vorwärts, The New World, and The Call were filled with articles about him, but bourgeois newspapers also gave him favorable publicity here and there: not only was he an anti-militarist, but he also played a role in the Russian fight for freedom, which Americans have always sympathized to.

Not only Vorwärts, The New World, and The Call were filled with articles about him, but bourgeois newspapers also gave him favorable publicity here and there: not only was he an anti-militarist, but he also played a role in the Russian fight for freedom, which Americans have always sympathized to.

Before Trotsky stepped on American soil, experienced reporters, who represented local newspapers, rushed to give him the third degree about his past and present life, his ideas, political views, plans—pretty much about everything, which he knew very well, knew very little, or knew nothing at all about.

The next day, almost all of the socialist newspapers published detailed reports on those interviews. Vorwärts wrote the biggest article, which filled almost half of a large-sized page. It was continued the next day, this continued so on and so forth.

During one such interview, Trotsky, who was being attacked by a half-dozen reporters and was touched by such a welcoming, noted: “I have never sweated like now when I am under the crossfire of those masters of their trade, not even when the police would give me the third degree.”

Newspapers published his portraits – both old portraits and those that were newly captured – in different poses and postures.

Soon after Trotsky’s arrival in New York City, there was a so-called Reception Meeting that was thrown in his honor at the Cooper Union.

Obviously, this meeting was promoted in every possible way, both in articles and advertisements, with the typical American razzle-dazzle.

Of course, I decided to go to the meeting. Although I was considerably late, there was no crowd outside despite my expectations. The room was almost empty, and I found a spot in one of the front rows.

I remember such a meeting in this very room in 1912, when the same Reception Meeting was thrown in honor of Deytch. The room was packed way before the announced time. Not only was the entire platform on the stage busy, all of the seats and aisles were taken, but there was also no space behind the seats, between the seats, and even on the window sills. Everywhere your foot would normally touch the floor, there was another person. This is how popular Deytch was, although he just came for the modest purpose of editing a small Russian newspaper.

This time, even the best-crafted advertisement, which touched the most sensitive strings of the emigrant mass, was obviously insufficient to make a person that lived all the way across the ocean and that was mostly unfamiliar to the vast majority of the public that normally fills up such meetings popular overnight.

The room was filling up slowly, and the meeting was forced to be opened with the room half empty, way past the announced time for the beginning of the meeting.

Again, in accordance with the established customs, before Trotsky took the stage, a lot of other speakers heaped their praises in different languages on the distinguished guest. However, who stood out the most was a representative of a German socialist newspaper, Lore, who raved and stormed (he obviously was an internationalist and hoped for Germany to win the war) to extol “our dearest teacher,” forgetting, however, that three-quarters of the audience did not know German and could not understand a thing he was saying.

How could Trotsky, who was writing in Russian, possibly become a teacher of the German Lore, who obviously did not speak Russian, and what academic articles he meant, remained his personal secret. Was it a little booklet “The War and The International” that enlightened the unpretentious scholar and editor?

When the audience was pretty much exhausted by this disorderly army of multilingual speakers, the man of the day took the floor and was welcomed by vigorous applause.

It is know that the popularity of the speaker is measured by the time during which the audience detains the beginning of the speech by showing affection in different ways: applauding, whistling, stomping feet, etc. – simple, yet noisy methods.

This is called “cheering.”

It is hard to tell how long this “cheering” would last if Trotsky, who had not yet developed a taste for the American treatment, did not disrupt it at the very beginning by expressing obvious signs of impatience and began his speech in the midst of the thunderous applause, when the signs of impatience did not work.

The audience settled immediately.

It is really hard to judge declamatory skills of your opponent. However, this speech of his had a great effect on me, just from the artistic standpoint. While listening to him, I experienced aesthetic pleasure, despite the fact that I absolutely rejected the idea the speech was based on.

I have listed to him many times after that. Sometimes his speeches were just average, sometimes they were good, and sometimes they were excellent. However, I have never heard any speech, which was like this one. Trotsky obviously thoroughly prepared for it, having this rare opportunity, and managed to get prepared for this one in a way he had never prepared and could not prepare. This speech had no rough demagogic methods of influencing the audience, at least those that for a cultured listener we can obviously call demagogic: the good theme made them absolutely excessive. He bombarded the audience with a great number of facts, which portrayed the terrifying realities of the war and the irrecoverable destruction, both material and spiritual, which it was inflicting at the moment and which would have threatened us in the future.

He thrilled his readers with terrifying reports that Paris was getting dark after six. And not because they were scared of the German zeppelins, he exclaimed in the heat of his enthusiasm, but because France was short on coal in its economic degradation; and women are wandering around the streets with bags where they collect coal leftovers to warm their freezing children and make a little warm food….

And spiritual degradation. To achieve victory at any price (in the midst of the German domination in the war), with the full acceptance of its no less barbaric allies, the French government, in order to save civilization, did not refrain from sending black African savages, who carried in their bags (and this is where Trotsky’s boiled-over pathos reached its highest point) cut-off ears of the German soldiers.

The spiritual degradation caused by the war could not go any further. He depressed the audience with the abundance of facts, each scarier than the last. His burning resentment and high-minded pathos were transmitted to the audience, which in turn, being ignited by his eloquence, joint in sincere indignation against the French government and its allies, who were leading Europe to such terrifying economical, social, and spiritual degradation.

However, all of those terrifying facts, no matter how serious they were, were nothing in comparison to the terror and degradation created by the civil war that broke out later in Russia. It is so true that you unconsciously start to doubt Trotsky’s sincerity when you realize that he and his friends, who managed to come to power, were the ones who inspired and led the civil war and tried their best to spread the sacramental fire of the civil war not across Europe, which had just started to embrace the peace that Trotsky was a big advocate for, but also to the rest of the civilized and uncivilized world, which has not yet been appended to this pestilent degradation.

However, his audience could not have known all of that then, and they could not have known about the forthcoming communist civilizing role in China and other doings of Trotsky and his friends, which were simply terrifying and easily overshadow all of those horrible facts that Trotsky was painting black to his New York audience.

That is why that aesthetic unity of their impression was not disturbed, and Trotsky’s triumph was complete. This part of the speech, where he spoke about the horrors of the war, was indeed dominating—both in length and content—as we have seen it before in speeches of all abstract advocates for peace by all manner of means, regardless of whether they were called “internationalist,” “antimilitarists,” or “neutralists.”

This speech was distinctive not because of the novelty of its ideas or profundity of thought, but because of its artistry.

Since war is such a horrible thing, it is obvious that every socialist should be dead against it. And those who accept war, who contribute to the extension of that war, even for a day in one way or another, is a traitor and defector of the working class’s business. And the socialists who remained loyal to their ideas could not have anything to do with those castoffs. They could not have anything to do with them, except for the grim struggle with those rabid enemies of the working class. He considered it necessary to make it clear in the very beginning, so no one has any doubts about it. This dissociation of socialists from traitors (he used those strong expressions all the time), regardless of their statuses and names—whether they were Plekhanov, Vandervelde, Thomas, Ged, etc.—is the first and foremost thing for every honest socialist.

Even I was impressed by the artistry of his speech, this logical transition from horrors of the war to abstract, starry-eyed, philistine and naïve antimilitarism quand meme was grate on my ears.

Anyway, here Trotsky did not tolerate any compromises and with the full power of his eloquence, he criticized the French socialist Thomas and others who shamed themselves for forever by joining bourgeois governments, accepted the war, consciously participated in that war and thus took the responsibility for all depicted economic, social and spiritual horror of it.

And when he started talking about nine Russian volunteers who were shot in battle because they did not obey some disciplinary rules, his eloquence reached the highest point, and his resentment had no limits. May the French government not try to make any excuses and shift the blame on the battlefield government—it carries the full responsibility for this despicable crime. And let Thomas comfort himself with the notion that he did not personally sign this death sentence. There was no actual signature of his on that document, but his name is engraved there with shameful indelible letters. And let those socialists who found it possible to reach a helping hand to such socialists like Thomas for any conjoint venture be damned. This is where his speech reached its climax. His scourging resentment seemed to be pouring out from the very bottom of his soul and was passed onto the audience, which was listening to him with breathless attention.

This happened at the end of 1916, just months before the Russian Revolution. And in the beginning of 1918, in the capacity of Field Marshal, and not just a modest immigrant, Trotsky reported in Moscow about instances of disciplinary disobedience in his army. There were no traces of the past pathos and pacifist resentment. He reported this calmly and busily, as it would be expected from a person in such a high rank, and thoroughly explained the steps that he took, including the arrest of those ten defaulters. Just on a side note, as if it was a small embarrassing lapse, he noted, “unfortunately they have not yet been executed.”

However, the audience of the Reception Meeting could not have known that, and they could not have known how easily the same Trotsky would soon kill not only dozens and hundreds guilty soldiers, but also their children and families, if those soldiers escaped the prosecution…Therefore, the artistry of the impression from his speech was not disturbed.

I anxiously listened to Trotsky in hopes of hearting his explanation as to why Belgians, Frenchmen, Serbians, and others should lay aside their weapons in the face of victoriously attacking Wilhelm’s army, and what kind of kind of benefits the Belgians, French, Serbians, Russians, and others, as well as those nations who were under the power of victors, would get out if it.

The answer soon followed.

It was as simple as could be. The horrors of the war were so extreme, baneful, and obvious to everybody, that there was no doubt that this would be the working class, which would come back from the war and would not be able to tolerate the political and social regime that committed those horrors. There is no doubt that they would organize uprisings against their governments and wipe them off the face of the Earth, together with the bourgeois lifestyles those regimes were carriers of, and establish a socialist regime. The working class from both sides experienced the horrors of the war. Therefore, upon returning home, they would create uprisings and revolutions everywhere, regardless of whether their government was the winner or loser in the war.

This opened my eyes, and everything became apparent to me. Since it is inevitable that the working class will organize revolutions and establish socialist regimes, there is no real difference as to which country wins and which country loses in this war.

The victory does not matter. What really matters is the all-round speedy return from the war. It is that simple!

What if they do not organize uprisings? Then…“Then,” Trotsky stated, viciously shaking his fist in the air, “I will become a misanthrope.” As you can see, he provided a solid guarantee there.

“An immediate ceasefire” is what is important. And all those “without annexations and contributions” and other propaganda are just small details, which serve as a honey trap to provoke a faster return from the fronts.

Why does this all matter when the whole of society, the whole world will be redeveloped in a completely new way and the entire map of Europe and the whole world will be completely redone in accordance with the program described in Trotsky’s “The War and The International”?

Needless to say, the speech had a huge success.

Trotsky soon gained huge popularity among the Russian community. Soon, he broke off relations with “social-patriots,” who made his journey to America possible and who welcomed him so warmly.

He became the editor in chief of The New World and quickly turned this publication into the second edition of Our Word.

———————-

Trotsky’s arrival in New York fell during the season of balls hosted by various organizations. Trotsky was a very tempting attraction for those organizations that managed to get him as a guest speaker, and, therefore, increase the profitability of their event. I saw and listened to him at a number of such events.

However, I have never spoken to him in person. His crisp and definite speech left no desire to do so. Besides, he was very inapproachable. He gave his speeches, provoked needed enthusiasm, got his fair share of triumph, and then left the podium. However, he did not join the crowd, did not blend in like a big beloved brother, but rather disappeared in a backstage cloud, surrounded by the atmosphere of a cold arrogance, which like a thick armor chased away even his most dedicated fans if they did not belong to the elite of the party and organization.

It was apparent not only to me, but also to those people who managed to get closer and get behind the amour. This is what one of the reporters of the local newspaper, who had the honor to interview Trotsky, shared with me: “In 1912 I interviewed Deytch when he came to New York to edit The New World. What a contrast between him and Trotsky! While Deytch is very approachable, and you soon feel like a good friend, despite the huge age difference, with Trotsky you always feel inferior as if you would be standing in front of an important nobleman who makes sure you don’t forget the distance between you and him.”

Meanwhile, upon his arrival in 1912, Deytch was already widely known as an old Russian revolutionary, who had already visited America after his escape from the penal establishment and as the author of 16 Years and Siberia, which was translated into nearly twenty languages. Not only was he known among the socialist audience, but also among other populations.

On the other hand, before his banishment from France, Trotsky was unknown to the non-socialist parts of the population, and he was only well known to a small group of socialist Russian immigrants.

However, the more arrogant he was, the more reverence he would get. The same reporter that I mentioned above once proudly told me that Trotsky had made a promise to initiate him. I must admit that I also wanted to see Trotsky somehow. We shared too many old memories and moments to simply ignore it. “When Trotsky visits you, tell him I said hi.” If Trotsky had any desire to see me, he could easily call me on the phone. That call never happened though.

“So, have you seen Trotsky?” I asked the next day. “Yeah, I recall him,” is all that Trotsky had to say about me after the reporter said hi from me.

It has been nearly three weeks since Trotsky’s arrival. One day I answer my phone: “Grisha, is that you? Do you recognize me? It’s me – Trotsky.”

It appeared that he had long wanted to see me and did his best to find me (if he really wanted, it was pretty easy to find me). He had found out about my appearances at the balls after I had left been gone, or after he had left the event. In one word, he wanted to see me and asked to set up a good place and time.

I went to see him. Our meeting was friendly, but not overly warm. There was no awkwardness, because both of us, as if we had a silent agreement between us, avoided any discussion on hot political topics (it was before the February revolution) and we already had a lot of other things to talk about. I learned a lot about my long-lost friends and acquaintances.

“How is Parvus doing?” (once Trotsky’s teacher and mentor), I asked.

“Working on getting his twelfth million,” Trotsky replied curtly.

I saw him several other times. We almost had never spoken about political topics. Once he made a remark about Plekhanov, obviously, not in the most favorable way. “Does that mean that he is a counter revolutionist, daddy?” his 11-year-old son, who was standing right there and attentively listening to him, asked. Trotsky smiled and did not reply.

Once he offered to play chess, apparently considering himself a good chess player. He showed himself to be a weak player and lost, which obviously upset him. He immediately offered to play another one. Once he won that one, he did not want to play anymore.

In this little episode, it was not just important that Trotsky did not want to play since the chances that he would lose were high, but also the fact that Trotsky could not learn how to be a good player. To learn how to play, he needed to play with superior players, and, therefore, lose multiple times. Trotsky could never afford that.

———————-

I have already mentioned above that Trotsky’s first speech opened my eyes as to his meaning of the slogan that he put into repeated by all “internationalists,” “immediate ceasefire.” It became apparent to me why he wanted that immediate ceasefire regardless of the way the war map looked at the given moment. However, it became less apparent to me why he was sympathizing Germany and its victories.

However, one lecture opened my eyes on that aspect as well. After drawing a picture of how modern European capitalist society, and even a society of the whole civilized world, is moving towards larger and larger unification, and how this development is leading to the destruction of economical independency and autonomy of certain countries, which in turn would strengthen their mutual dependence. He draws the right conclusion that the strengthening progressive connection and dependency between civilized countries is inevitably leading to a necessity for a political unification. And any attempt to preserve independence of one country or another, whether it be Belgium, Serbia, Austria, France, or Russia, will inevitably be politically, and, therefore, socially reactionary. Thus, any discussions about defense are highly harmful and reactionary. “Social-patriots,” with their ideas about protecting the given Motherland disturb the judgment of crowds, restraining them from a sooner ceasefire.

It is just one country involved in the war, which is so far ahead in its’ social, economic, and cultural development that it is the only country that could possibly, in the case of victory, make unification of the civilized world from “the top” possible, and, therefore, play a significant progressive role. This country is Germany.

Trotsky was very cautious with his wording. Obviously, he did not want to sound clearer, so he does not openly appear to be a Germanist. I listened closely to his speeches to get and not lose the main theme of his reasoning. He did not have a strong desire to make direct implications from this idea and clearly communicate them to the public for some obvious reasons: at the time he hoped to make that unity happen through revolutions and uprisings in certain countries. He was hiding the idea of the German domination—maybe away from himself—on the back of his consciousness, like a plan B in case plan A fails.

Like an experienced strategist, he could not really talk about the perspectives of the unlikely, according to his beliefs, failure, so it does not stay in the way of victory.

“The bourgeois method of resolving current issues is war. The working class method is revolution,” he pronounces in his pamphlet “The War and The International.” As a “revolutionist” he prefers the second method and only if it fails he agrees to the first method, where oppressive Germany conquers the world.

After signing a peace treaty in Brest with oppressive Germany, which gave Russia a good chance to feel its heavy paw, the Bolsheviks were knocked off their feet for a while. Not only the external, but also the internal situation did not look too promising for the nearest future. The new Russian Messieurs were in a pretty grim mood. And when they found out that Japan, with the full support of its allies, was going to attack Soviet Russia, Trotsky stated in the press. “If we are threatened by invasion of the imperialist Entente, we will form an offence-defense alliance with Germany (after smashing Russia, Wilhelm’s government had still been victoriously fighting the Allies), like with a more progressive imperialist country as opposed to the reactionary Entente.”

Therefore, the cautiously guarded from himself and others reserved the idea of the German domination started to become apparent and assumed the similitude of the reality.

———————-

Sometimes returning from the lectures, Trotsky would condescend to me and give me a friendly clap on the back telling his people, “This is my old friend who needs to stay in France for a couple of months to become a good socialist.”

One time, using our alone time, I started to interview him about his certain “internationalist” colleagues in New York. There was someone called Semkov, an uneducated person with a naturally loud voice and overly “revolutionist” manner of speech. He had a special talent to speak in “revolutionary” phrases without rest for an unlimited amount of time, although those phrases had no logical connection. As an uneducated person, he did not know any thorny subjects or questions, and everything was clear and easy for him. He could never been caught off-guards. He was always ready to object any question on any subject. His ecstatic speeches always made such an impression, as if he would stuff his pockets with random phrases from Lenin and Trotsky’s catechesis along with cigarettes and matches when he would rush out of his house to attend yet another meeting. Once he appeared at those meetings, he would start to turn his pockets out and show off all of this stuff without even carefully listening to the opponents’ arguments. His phrases would be pulled out of context, without beginning or ending, and the main body, however, had a more impressive “revolutionist” effect and provided him with a great success among “revolutionist” crowd. He was much appreciated in the “internationalist” crowds, and he was considered an irreplaceable and valuable member. This star, all spite aside, I asked Trotsky about.

“No matter what he is, “ said Trotsky as always giving full value to each word, without even thinking, “When the time comes, Semkov will be there, where needed, unlike N.N. (Trotsky’s permanent opponent at all meetings) will always be there where not needed.”[1]

[1] Later, following the activities of Trotsky’s former New York associates in the Russian newspapers, I had the true opportunity to see that Semkov was always “there where needed,” holding “there” in a high position.

Great article. Thanks!