Of all the people Leon Trotsky met during his 1917 ten-week stay in New York City, few were more personally hostile then Grisha Ziv. Continue reading “Grisha Ziv on Trotsky, 1917, as translated from the original Russian”

Of all the people Leon Trotsky met during his 1917 ten-week stay in New York City, few were more personally hostile then Grisha Ziv. Continue reading “Grisha Ziv on Trotsky, 1917, as translated from the original Russian”

In digging into the story of my grandparents and their flight from Eastern Europe in the 1920s, I was surprised to learn that two giants of the age held our fate dangling at whim at one key point. One was Polish leader Jozef Pilsudski, whom I’ll talk about next time. The other was Lev Davidovich Bronstein, better known by his revolutionary nom du guerre, Leon Trotsky.

In digging into the story of my grandparents and their flight from Eastern Europe in the 1920s, I was surprised to learn that two giants of the age held our fate dangling at whim at one key point. One was Polish leader Jozef Pilsudski, whom I’ll talk about next time. The other was Lev Davidovich Bronstein, better known by his revolutionary nom du guerre, Leon Trotsky.

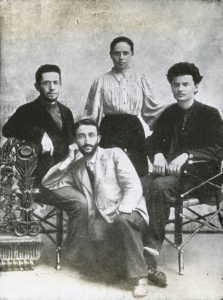

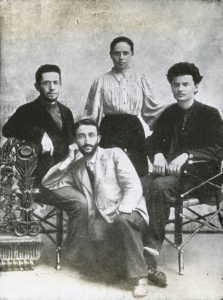

What a strange man, Trotsky, a zealot among zealots. Look at him in this 1919 photo, strutting about as Commissar of War in the new post-1917 Bolshevik Russia, rousing his Red Army troops. He spoke in spell-binding sentences, brilliant as a writer, tactician, or theorist. People loved him, hated him, and feared him. Born and raised Jewish, he rejected it as a young man as bourgeois fluff. “I am a Social Democreat and only that!” he insisted when asked.

In 1920, Trotsky was still neck deep defending Red Russia in a gruesome civil war, pitting the new Leninist regime against not only White Russian reactionaries but also an international expeditionary army from Britian, France, Japan, America, and other countries. Still, that spring, on orders from Moscow (Trotsky fought the idea at first), he launched a full-scale invasion of the newly-created country of Poland — what he called a land of “oppression and repression under a cloak of patriotic phraseology and heroic braggadocio.” The plan was to spread revolution both to Poland and through Poland, reaching German and the west.

By summer, Trotsky’s Red Army had knocked Poland’s defenders on their backs, sending them into heavy retreat. Soon they were closing in on Warsaw itself for a knockout blow.

This is the war that my grandfather, Rubin Mendel Bronnfeld, then a 29 year-old father of five young children living in a tiny village shtetl called Zawichost, was asked to fight. That spring, the Polish army, desperate for soldiers, expanded military conscription to include 30 year-olds — even Jews like him. By this point, my grandfather had already seen two brothers killed in military clashes, but that wasn’t his main reason for objecting. Polish independence in 1919 had been accompanied by a wave of anti-Jewish riots, pogroms, killing hundrds. Many of the worst clashes were prompted or carried out by Polish soldiers, always citing some unproven Jewish provocation.

My grandfather faced a gut-wrenching choice: whether to risk his life for a country that had given his people pogroms and oppression, or whether to leave his family’s centuries-old home and follow a wild scheme of underground flight across war-torn Europe, hoping eventually to reunite with wife and children in faraway Amerca.

Poland’s defense against Trotsky’s 1920 invasion would be brilliant and heroic. It would stand firm and defeat the Red Army in dramatic fashion in the Battle of Warsaw, deservedly remembered in Polish history as the “Miracle on the Vistula.” But by forcing my family to uproot itself and flee, it would save us from death in a far worse crisis just over the horizon, the Holocaust of World War II.