|

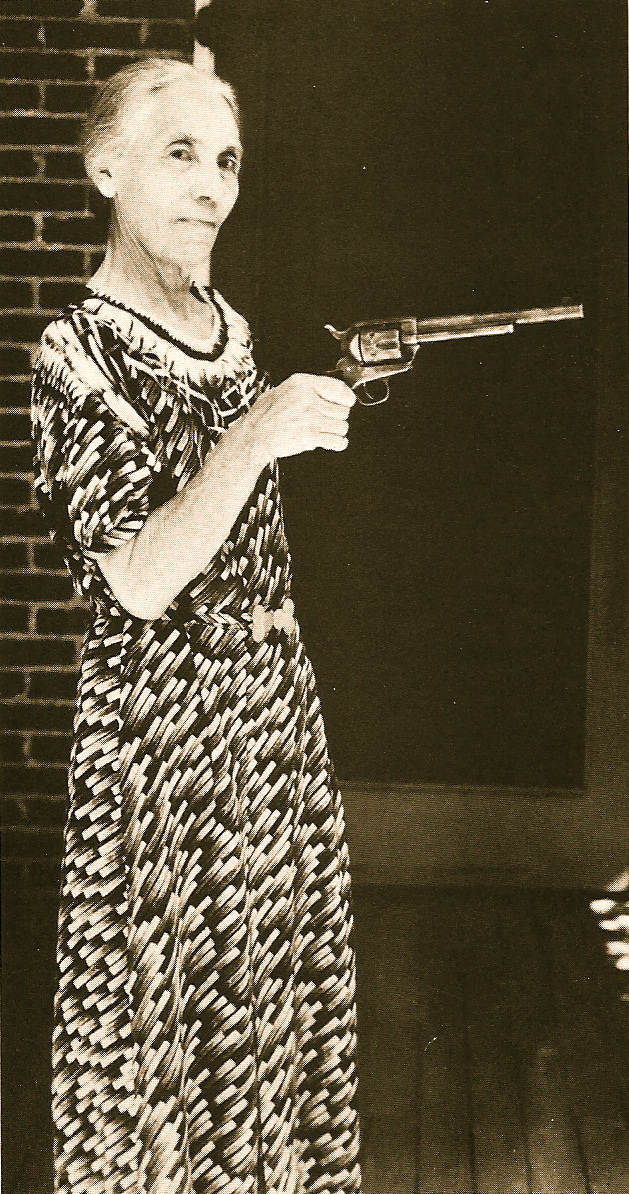

| Emma Goldman, mid-1890s. |

The police in Philadelphia held Emma Goldman for almost a week after her arrest in August 1893, before they could arrange extradition to New York City. “I was weighed, measured, and photographed,” she recalled. On the train ride north, one detective tried to befriend Emma. He offered to get the criminal charges against her dropped if she would spy on some of her radical friends. She told him to go to hell.

|

| Oakey Hall, Emma’s lawyer, as Mayor of NYC in 1870. |

In fairness, Oakey Hall, then 67 years old, gave his young client a first-rate defense. The New York grand jury had indicted Emma Goldman on three counts of incitement to riot, based on her August speech to the unemployed workers at Union Square, her telling them to steal bread from the rich people on Fifth Avenue. Hall built his defense on three key points: that police detectives had made mistakes in translating Emma’s speech from German to English, that the Union Square meeting itself was perfectly legal, and that her words were protected under the US Constitution as Free Speech.

Emma on the Stand

But the trial’s highlight came on its third day when Emma Goldman herself took the stand to testify. The chief prosecutor, Assistant District Attorney John F. McIntyre, decided to use his trump card. He would show the 12-man jury that, no matter what she said in her speech, this woman was a dangerous radical zealot. Emma herself was exhausted by this point in the trial. One reporter described her eyes as being “misty and restless, and there was a tremor in her hands” as she took the stand.

“Do you believe in a Supreme Being, Miss Goldman,” he said, causing gasps in the packed courtroom.

“No, Sir, I do not,” she said. What did God have to do with the criminal case? No matter.

The prosecutor went on. “Do you believe in the laws of the State?”

“I am an anarchist, and against all laws,” she answered. “My theory is that the Legislature and the courts are of no use to the mass of the people. The laws passed help the rich and grind the poor.”

“Didn’t you tell your hearers [in Union Square] to take bread by force if they couldn’t get it peaceably?”

“No. But I think the time will come, judging by what has happened, when they will be compelled to do so. That is what I told them on the night I spoke.”

Then he turned back to anarchy itself, that strange foreign-sounding word. Anarchists in Europe back in the 1890s threw bombs and assassinated kings. Even in the US, the Haymarket affair in Chicago — just six years earlier — still scared the socks off most Americans. The prosecutor asked about one radical recently arrested with a bomb. “What do these anarchists want with dynamite bombs, anyhow!” he asked.

“Why, they want to use them in the great war if the social revolution ever comes,” said Emma Goldman.

“Would you use dynamite?”

“I do not know what I would do. The time may come when it may be necessary to use it.”

The testimony was devastating. Emma had given the prosecutor all the ammunition he needed to paint her as a violent, godless, unpatriotic malcontent who deserved prison whether she committed a crime or not. Oakey Hall, in his final plea to the jury, did his best to put Emma’s words in a positive light. The anarchist, he explained, “believes in co-operation and the common ownership of property. Anarchy dislikes the rich and the monopolistic, but surely this is no crime.”

The Verdict

|

| Emma Goldman at time of her depotation from America, in 1919. |

Emma Goldman refused to appeal either the verdict and or her sentence of one year’s confinement at the penitentiary on Blackwell’s Island in New York’s East River, a spot now called Roosevelt Island. Wild rumors circulated that radical anarchists might bomb police stations or try to manage her escape, but nothing happened. Once behind bars, Emma found relief from the prison gloom by working in the hospital, starting a life-long interest in hygiene and medicine. She read books and delighted when radical friends came to visit.

On her release, Emma Goldman would speak loudly as ever, start her magazine Mother Earth, write essays and books by the dozens on topics from politics to labor to feminine hygiene to marriage to war and peace. She would be jailed many times, including after the assassination of President William McKinley when the shooter, a self-described anarchist named Leon Czolgosz, mentioned he had been inspired hearing her speak. On American entry into World War I, Emma Goldman spoke out against military conscription and was jailed under the wartime Espionage Act. After the war, she, along with Alexander Berkman, was deported to Russia – one of many abuses from the 1919 Red Scare. Still, she always considered America her home, and on her death insisted on being buried in Chicago, near the tomb of the Haymarket Anarchists.

Every American political activist today of any stripe — liberal, radical, conservative, tea party, whatever – owes a deep “thanks you” to Emma Goldman for practicing the most basic truth about our rights under the Constitution. Simply put, it’s this- Free Speech: Use it, or Lose it.

If you’ve never heard of Emma Goldman because, like Victoria Woodhull, nobody bothered to mention her in your high school or college history classes, don’t let them get away with it!! Before Women’s History Month is over, check out one of these good books: