|

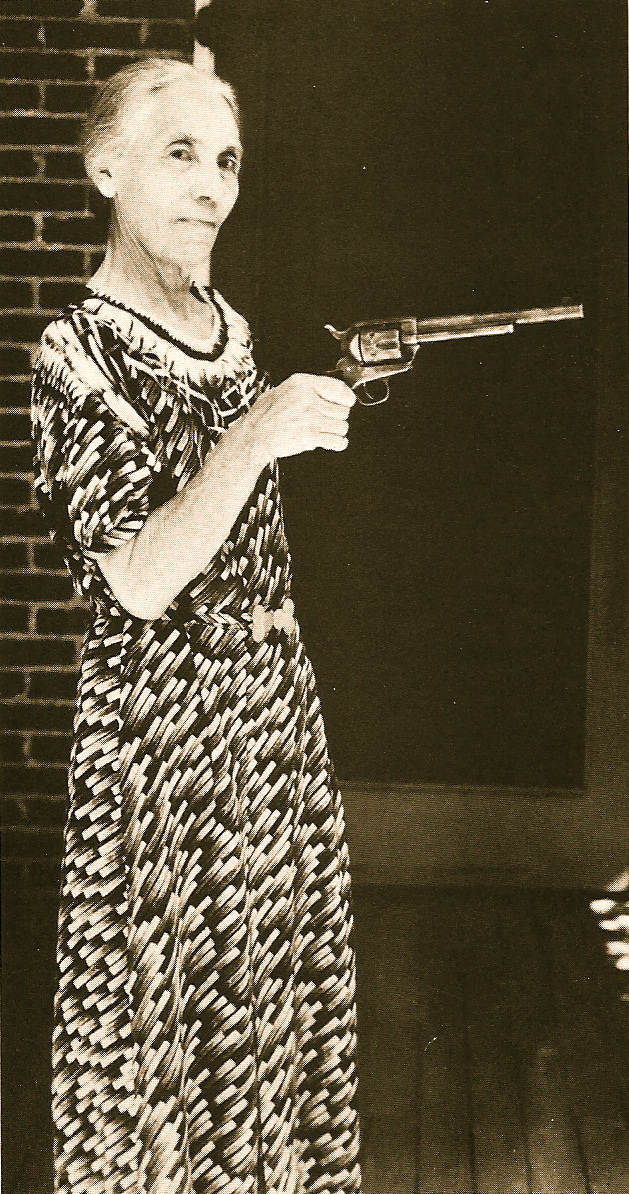

| Victoria Woodhull — in typical radical pose for the 1870s: no bonnet, no shawl, and short-cut hair. |

Free Love:

may, to love for as long or as short a period as I can; to exchange that love every day if I

please…. and with that right neither you nor any law you can frame has any right to interfere….”

The Boston crowd screamed wildly — half booing and hissing, half cheering — when Victoria Woodhull shouted these words in January 1872. Not surprisingly, more Americans back then saw her as the “Mrs. Satan” in the cartoon below, leading poor women to sin and poverty, that as the respectable face in the handsome photo of her above. Victoria Woodhull earned her spot as the most noticed, emphatic, assertive, talented, envied, and (as a result) vilified, mocked, and slandered women in the country during the early 1870s, that free-wheeling period after the Civil War called the Flash Age.

|

| Woodhull as “Mrs. Satan” in 1872 Harpers Weekly. |

Fearless and with a sharp eye for publicity, Victoria quickly recorded a remarkable string of firsts:

- She and Tennessee started the first women-owned brokerage firm on Wall Street, with help and trading tips from Vanderbilt;

-

- She then used the money they made to start a newspaper, Woodhall and Claflin’s Weekly, favoring free love, women’s rights, and a ten-hour work day. In December 1871, she published the full text of Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto, its first appearance in the US;

- She became the first women to testify before the US Congress in Washington, D.C., making the legal case that the 14th Amendment gave women the right to vote (the argument Susan B. Anthony would go to jail over in November 1872);

- She became the first women to run for President of the United States, nominated in 1872 by the Equal Rights Party. Notably, she was under age, and her VP running mate, Frederick Douglass, supported one of her opponents, Republican Ulysses S Grant.

The Adultery Scandal:

The Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, pastor of Brooklyn’s popular Plymouth Church, was a uniquely well-liked public figure in America at the time. His Sunday sermons reached far beyond his packed church, carried in newspaper columns across the country. Dynamic and handsome, he was also cheating on his wife Eunice, the mother of his ten children. Beecher had seduced the wife of one of his church followers, Theodore Tilton, and reputedly many others as well. Eunice Beecher, distraught over the affair, finally told her friend Susan B. Anthony about it. Anthony told the story to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who made the mistake of repeating it to Victoria Woodhull.

|

| Woodhull appearing before Congress’s House Judiciary Committee, from Leslie’s Illustrated, February 1871. |

Woodhull was appalled. This same Henry Ward Beecher had publicly mocked her for her own “free love” speeches, yet here he was doing the same thing — only in secret and at his wife’s expense. Victoria Woodhull, decided there was only one thing to do with such a hypocrite coward. Call him out !!!

And so, in the Woodhull and Claflin’s Weekly of November 2, 1872, Victoria led with a splashy front-page column exposing all the dirty laundry of the Beecher family, calling Reverend Beecher himself a hypocrite, and daring him to sue.

Slanderous? Tawdry? Intrusive? None of her business? Yes to all these things. Today we call it “sleazy tabloid journalism” — but that alone was not enough to put Victoria Woodhuill in jail, even in 1872.

Comstock had already run a few small-time smut dealers out of business, and drove one of them to suicide. He now read Victoria Woodhull’s article about Henry Ward Beecher’s adultery and decided to make a bigger score. Anthony Comstock decided that, to his eye, the article was obscene. Among other things, it contained the words “token” and “virginity.” And it traveled through the US mail — a crime. He quickly obtained a federal arrest warrrant and instructed two burly marshals to waylay Victoria and sister Tennessee one day at their office after returning from a carriage ride.

Behind Bars:

Victoria and Tennessee quickly found themselves in big trouble, placed under arrest and held for questioning at New York’s federal courthouse. Passions ran high at this point against “Mrs. Satan,” an uppity woman talking Free Love, mocking politicians, and now staining the good name of a church leader. “An example is needed, and we propose to make one of these women,” said U.S. Commissioner Osborn setting their initial bail at an eye-popping, unaffordable $8,000 apiece (about $200,000 apiece in modern money).

The authorities immediately took Victoria and Tennessee and locked them up inside New York’s Ludlow Street Jail. To make things worse, the police also arrested Victoria’s husband (the current one) and two men who worked at the Weekly, and destroyed thousands of copies of the newspaper. Typical of 1870s newspapers, the New-York Times, in covering the initial court hearing, failed to even notice the gross violation of free speech underway, focusing instead on Victoria’s clothes (a black dress with purple bows) and facial expression (she looked “grave and severe” while Tennessee looked “indignant.”).

The Reverend Henry Ward Beecher denied everything — causing major grumbling among people who knew better — and the public backed him. A federal grand jury indicted Victoria and Tennessee under Comstock’s anti-obscenity law, and one of Beecher’s church friends filed a libel suit as well. It would take a full month of legal wrangling, until December 3, for Victoria and her sister finally to be freed on bail that, for the multiple cases, ending up totalling $16,000 apiece. During this entire time, the judge never allowed Victoria to answer the obscenity charge in a public hearing. Instead, her only chance to speak came through a single letter she snuck out to the New York Herald in which she declared herself “sick in mind, sick in body, sick in heart…. because I am a women, I am to have no justice, no fair play, no chance through the press to reach public opinion.”

The legal costs almost bankrupted Victoria Woodhull and her newspaper. Most auditoriums now black-listed her speeches. Still, she left Ludlow Street Jail full of fight. She immediately issued a new edition of Wooodhull and Claflin’s Weekly detailing all the legal conniving and used the publicity to pack out-of-the-way venues for her new featured speech performance: “Moral Cowardice and Moral Hypocrisy, or Four Weeks in the Ludlow Street Jail.” Comstock had her arrested two more times, resulting in another week in the Ludlow Street Jail, a night at The Tombs — New York’s maximum security prison — and thousands more spent in bail money. But when Victoria finally had the chance for a trial on the original obscenity change in June 1873, the judge found the case so weak that he threw it out before it even reached the jury.

And more: Theodore Tilton, husband of the women seduced by Henry Ward Beecher, finally had enough of the Reverend’s evasions and went public. His lawsuit against Beecher over the affair would produce the first great media circus celebrity sex-scandal trial in America. (The trial ended in a hung jury, a technical win for Beecher.)

All all this was not enough to save Victoria Woodhull. After the Beecher-Comstock episode, she found her reputation destroyed, constantly harrassed by lawsuits and slanders. In 1877, she finally called it quits and sailed to England where she married a rich British blue-blood banker named John Biddulph Martin. Here, she gave lectures, started a new magazine (The Humanist), and moved to remote Bredon’s Norton where she made her home a refuge for wayward eccentric Americans, then to Brighton near the sea. A spritely old lady until 1927, she became the first women to drive a motorcar, to predict trans-Altantic flight, and to predict wireless radio.

Next up, Emma Goldman…..